A New American Renaissance

On Benjamin West, Incubator and Coordinator

In order to dive into an appreciation for the incredible figure of Benjamin West (friend of Ben Franklin, mentor of Samuel Morse, and leader of an American renaissance movement in England), let’s start this essay by reviewing an interesting painting from 1795 titled ‘The Royal Academicians’, the header to this piece.

In the center is the president of the English Royal Academy of Fine Arts who trained Samuel F.B. Morse, and he is surrounded by different artists and artwork from the British Royal Academy.

That president and co-founder of the English Royal Academy is named Benjamin West.

Benjamin West was heralded, and for good reason, as the greatest living painter during his lifetime, and is a man of untold anomalies.

He was born in 1737—the same year as King George III, and was a Quaker, but that is not too anomalous.

However, when we ask WHERE was this man born? Our story gets very interesting… since this President of the English Royal Academy of Fine Arts was born in Pennsylvania!

He’s a Quaker born in Pennsylvania, completely self-taught, having received no formal training.

West actually learned how to paint because his family was very friendly with many Delaware natives. And they taught him to paint using clay and bear wax, bear grease from the lake nearby his house. And that’s how he learned how to paint.

Within a short time, this young man found himself in the same networks that were created by Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Philosophical Society.

West’s father was a very close friend of Ben Franklin, and in 1751 or 1752, his father, who ran a boarding house, made his home the very first building in the world to put up a lightning rod.

When he was brought into England, there were patrons, friends of Ben Franklin who saw the man’s talents, his family and broader Quaker community did not want to let him paint because the Quakers, the strict Quakers, basically saw all forms of the arts as being corrupting because they awoke passions, and passions were assumed to be equally dangerous for a fallen sinful mankind.

This is why they actually had to have an emergency meeting to address the question: ‘what do you do with this kid who has obvious talent and ambition?’ And they had a long, drawn-out meeting all night long where they finally came to the conclusion that ‘if God gave him this skill, and even though we agree that painting has tended to be something which doesn’t make you a better person, who’s to say it can’t make you a better person if done right?’

And they arrived at a pretty enlightened decision by saying, ‘maybe he’s the one who can bring painting to another level where it can make people better.’

Having received the seal of approval from his family and broader community, West found support from some of Ben Franklin’s friends, who sponsored his voyage to Europe after seeing his painting The Last Days of Socrates [seen below], featuring the great philosopher taking the Hemlock, which was his first sort of big painting in America.

It is admittedly a far cry from his later works, but it’s an interesting thing to choose to do as a teenager.

Franklin’s network sponsored his voyage to France in 1769 then to Italy, where he studied the great classics, the masters, and after two years of doing that, he was going to take a little bit of a sojourn to London before his planned return home. However, while in England, he caught the attention of some very interesting people, including one of the advisors of King George III himself.

He must have made quite the impression, because after this meeting, West quickly began to rise in influence within the English cultural scene, and he began to do some things that very few people appreciate to this very day.

This story has really been obscured from the history books, and I sincerely believe that were it not for the incredible world of the Canadian-born historian Pierre Beaudry, who made this chapter possible through his pioneering studies, then Benjamin West’s story would still be hidden to this very day.

Here is a 1790s self-portrait of Benjamin West.

Benjamin West is a man of true classical Platonic tradition, and in order to get an insight into West’s character, we will have to explore the clues (that is to say, the anomalies and ironies) which he carefully embeds in his artwork.

In the mind of all Platonic renaissance artists, the language ironies, is a language of communication designed to invoke important ironies that challenge our preconceived assumptions about reality via anomalies that could awaken first a sense of perplexity, then wonder and finally, discoveries in the minds of an audience.

Now, admittedly not all of West’s art students followed this advice, but many of them, including Samuel F.B. Morse did it masterfully.

For our first anomaly, let us review two paintings. The first is a self-portrait of a young West painted in 1770.

By this time, West had only recently arrived in England and received the patronage of King George III. He had also become a founding member of the English Royal Academy of Fine Arts that had just been set up in 1769, and in 1791, he actually became that organization’s president!

Now, seven years later, in 1776 he does another painting of himself that looks remarkably similar.

Do you see anything peculiar here?

It is noteworthy that this self-portrait is composed several weeks after King George III had received the Declaration of Independence, and the war had officially really gotten underway.

Why would he do this?

What is the same and what is different between these two very similar paintings separated by seven years?

Does anything pop out?

What about his eyes? Is there a difference in them?

His eyes look darker in the later 1776 portrait.

But even more than simply being darker, or cast in shade, they also appear more worldly and wise when contrasted with the younger portrait where his eyes are lighter, more wide-eyed and more naive.

By the time 1776 rolls around, you know that he has seen a lot and learned to navigated corridors of power and intrigue of England’s royal courts.

I think there is also something significant in West’s pulling of his tight collar as well which occurs in both paintings.

He is, after all an American, and these collars which were British formal attire were known to be pretty suffocating and it wasn’t customary to have these like tight, polite collars in America. I think his pulling on it is sort of a symbol of the tightness of the formalistic English culture.

Keep in mind, he never ends up returning to America as planned. He lives out his life in England, and never goes back to America. And he’s called a traitor for this by Americans who lived through the revolution.

He’s attacked as an American traitor, and ironically, he’s also attacked by the British for being an American spy. That latter accusation may be a bit more true.

Do you see any other anomalies in these two paintings?

The composition of the rag hanging over the canvas frame he is holding in his left hand has completely changed from one painting to the next.

On the second portrait, the rag looks very different from the first one, which has nothing on it, whereas in the second one, there is definitely something there.

It isn’t easy to discern what that image is on the rag, and it took a really long time for me to figure it out, but it is a human figure, and without the incredible studies of Pierre Beaudry, for whom I am eternally grateful, I may not have ever realized what this is.

This anomaly is a big one, and intentionally placed there to create the perplexity, the sense of irony that you are now feeling.

So what is the discovery that West wants you to make?

To answer that question, we need to look at another painting by West composed in 1770 titled ‘The Death of General Wolfe,’ featuring a rendition of the 1759 death of the famous English general at the Battle of Quebec during the Seven Years War.

Does anybody recognize the two figures on the right?

Do those two figures and those two figures on the right side of the painting and those two figures on the rag look at all familiar?

These are the figures featured on the rag in West’s self-portrait of 1776!

So that priest standing on the right, on the right side of this painting, next to the soldier in the red coat have some importance in West’s mind.

West appears to be saying something about this moment, this painting composed six years earlier, showcasing an event that happened twelve years earlier across the Atlantic Ocean. And the fact that he’s doing this in 1776 is not a coincidence either.

Now, Benjamin West is most famous for his history paintings. He was a history painter, and that’s what many of his students became as well.

He had a philosophy of history painting, that society will value the memories that it has.

And the purpose of the painter is to convey those moments of his collective past and enshrine them in such a way. that universal lessons of who we are will be learned. This is a powerful philosophy that transcends the narrow limits of historical paintings which have been artificially imposed onto the field in our modern era, which presumes historical paintings must be either objective, sterile renditions of the past, or emotionally manipulative propaganda, and nothing more.

Okay, so what else do we have here?

What would have been important historically in this moment in 1759?

Well clearly, like I already mentioned, this is The Battle of Quebec at the Plains of Abraham.

The French had just lost, but as much as the French had just lost, General Wolfe, who was a young man, had also died at that battle.

This was a strategic moment because it was the decisive moment that the French empire lost its stranglehold in North America, giving the ability for Benjamin Franklin’s networks to organize for what would become the American revolution.

These networks led by Franklin had already been planning out the conditions of declaring independence for decades, as the late historian Graham Lowry brilliantly demonstrated in his magnum opus ‘How the Nation was Won: volume 1’ (1630-1757).

In order to create the conditions that would be ripe for the declaration of Independence, it was understood that Quebec, after it fell to the British, would likely side with the republican cause against the British Empire. The French Canadians themselves had almost unanimous consent that the British were tyrants. They didn’t like the British in general. They didn’t like the British Empire, but they got along very well with the other colonists of the thirteen colonies, and it was understood that Quebec was going to be the 14th member of signing the Declaration of Independence.

That was pretty well understood, and that’s why Benjamin Franklin put so much of his work into going up to Quebec in 1774 to organize the elites and the people to be a part of it. That’s also why Franklin set up Canada’s first postal service in 1759, which ensured that lines of communication could be established across Quebec as a pre-condition for both organizing the revolution, but also elevating the culture of Canadians.

However, certain games were played and certain bribes were made that ensured that that did not happen, as we know, and history unfolded a different way.

But this was a very deciding moment, and it also features something that most British historians chose to ignore which revolved around a figure who was involved at that Battle of Quebec by the name of William Johnson. This man was featured in West’s painting, along with an array of other individuals, but in reality, no one was actually present, or even close to General Wolfe as he died.

You see, General Wolfe had gotten shot, and he died behind a bush with two other people in attendance. However, Benjamin West chose to organize his composition in a very different way for a reason. This figure of William Johnson who is featured wearing native stockings, and moccasins is a very special person to both Benjamin West as well as to the entire battle of history.

One thing that is noteworthy about Johnson is that he was an Irishman who moved to New York in 1738.

And he didn’t play by the typical British stuffy customs or rules of behavior.

He did things very differently, but very effectively when he started organizing treaties with the natives and working with the natives, with the Six Nations, the Mohawks and the Iroquois. He respected their customs and languages, and built sincere relationships with many of these tribes that had been manipulated by the Jesuits for generations.

Johnson is a figure who stands out, because while all of the other British soldiers and officers have this blanket tendency to treat the native populations as sub-human savages, this guy is integrated very much culturally with the native.

In the painting, West showcases him with the native stockings, moccasins. He’s renowned for being somebody who completely respected the native culture. He learned several different native dialects. And by 1742, he was made a Mohawk civil chief.

He was made the colonel of Six Nation Mohawks. The Mohawks even requested that he be the official representative of the British to them, because they couldn’t work with anybody else. Nobody else respected the natives and visa versa.

And you have him pointing to the soldier running towards the cluster in our vision, holding a fleur-de-lis and declaring victory.

I think one of the things that’s also important that Benjamin West does here is he juxtaposes the strength of a Mohawk soldier, who were instrumental in this battle against the French.

To restate: up until this point, the Jesuits which controlled the French territories of the Americas, had done the most work in organizing a lot of alliances with different native bands, and had done an immense amount of damage manipulating these groups against each other, and sometimes against colonists. But the danger for the English republicans was that IF the Mohawks or Iroquois were going to be allied with someone during the war, then in all probability, it was going to be the Jesuit-run French.

But largely through the efforts of William Johnson, the republican intelligentsia began to gain a creative hold over their French adversaries, and also began to build a respectful relationship with native groups.

And when the Mohawks and Iroquois chose to fight alongside the English against the French, the scales of battle were tipped entirely.

So that was extremely important.

The additional fact that you have this Native American warrior featured in the center of the image, almost carrying more weight than the dying General Wolfe, we are struck by a contrast between the weakness of the British Aristocratic Wolfe, which may also symbolize, in a subtle way, the dying British Empire itself.

The Platonic ambiguity used by West is brilliant and intentional.

If you’re an American republican or you’re a British aristocrat looking at this scene, you will get two very different messages.

And that was one of the brilliant things of great artists, is you can walk in the realm of ambiguity and communicate two different messages to two different people who may not understand what your actual intention is.

To re-emphasize, Benjamin West painted this in 1776, and at this time, it was still unclear what the outcome of the war would be.

The other thing that made West’s treatment of the Battle special, and this is something that many people would take for granted today, is up until this 1771 painting, hardly a single history painting had been done using contemporary costumes. Especially in the “high cultures” of England and France, but really across all of Europe, every time that a history painting was done, it had to involve the costumes of Greco-Romans from 2,000 years earlier.

It’s weird to think about today, because it feels so obvious, and artists have been doing this for so long. But this was really a standard of behavior among the art community in the 18th century.

And West was even threatened by the establishment.

He was told, ‘you’re never going to get a commission again if you break from the rules.’

But he did it. And he wrote to a friend, saying,

“The event intended to be commemorated took place on the 13th of September, 1759 in a region of the world unknown to the Greeks and Romans, and at a period of time when no such nations, nor heroes in their costume, any longer existed. The subject I have to represent is the conquest of a great province of America by the British troops. It is a topic that history will proudly record. And the same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil of the artist. I consider myself as undertaking to tell this great event to the eye of the world; but if, instead of the facts of the transaction, I represent classical fictions, how shall I be understood by posterity?”

Through the power of his reason, talent and insight, West soon won over his audience. And when George III was asked to chime into the debate, he was actually so impressed with West’s line of reasoning and talent that he purchased the painting, settling the debate once and for all.

The meta-theme deployed by West and all leading early republican intelligentsia at this time revolved around the problem of resolving the discontinuities in European Americans with their civilizational proclivities, and the First Nations with their unique civilization. How to harmonize them to create a society that could respect individualism of identity and diverse cultures while at the same time collaborating around a transcendental idea of a common freedom driven humanity.

And part of the understanding has always been that it will only be when American culture can understand and respect the Native cultures that, instead of just treating the Natives like they’re subhuman, clearing them from their land or sticking them into invisible prisons called ‘reservations’, but instead really treat them like sacred partners in a common mission… only at that point will America acquire the real moral fitness to survive.

This is why James Fenimore Cooper focused so much on these themes in his popular tales later.

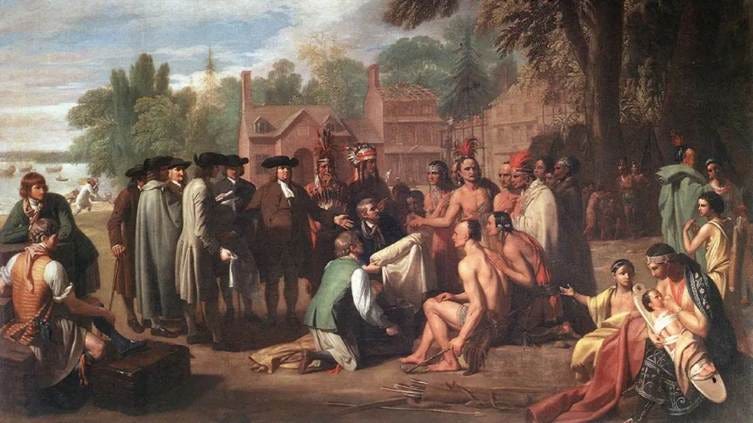

This battle is expressed in another painting by Benjamin West, also completed in 1771, celebrating the famous Penn Treaty of 1682 in Pennsylvania.

Let us recall that West himself was from Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, and his grandfather was a close friend of William Penn (1644-1718). William Penn was the founder of Pennsylvania Colony, and was one of the key leaders of the Leibniz/Jonathan Swift’s networks in America.

Penn had acquired a certain area of land, and he was committed not to just using it for wealth extraction the way the British Empire had expected, but rather developing the culture, economy and populations along the lines set forth by John Winthrop Jr and John Winthrop earlier.

The great historian Graham Lowry goes through a lot of William Penn’s work in his, How the Nation Was Won.

Now Benjamin West’s painting featured the signing of a historic treaty between the Delaware natives and the English settlers in 1682.

What needs to be understood, is that William Penn did not HAVE to sign this treaty. After all, he had been given sole dictatorial authority by the Crown Charter over the land of Pennsylvania.

He didn’t have to pay the Delaware natives anything if he didn’t want to. He could have used the “might makes right” principle of empire.

This nasty practice had been done many times before, and it was done many times afterwards… but he chose not to do it.

Instead, he chose to work out an extremely important and unprecedented treaty, paying the Delaware people very much in a variety of ways, and ensuring that they had total freedom to use the land as they saw fit, even after the Europeans began to settle down.

West’s painting features a moment where textiles and other gifts are being offered by Penn’s negotiators. Not alcohol or guns, but textiles and other goods. We also see the famous cedar tree in the background, which is where the actual signing of the treaty took place.

What is painted is not the signing, but the respectful negotiations leading up to the signing.

There is a certain anomalous shadow cast upon the main figures in the center of the painting, and it is difficult to identify its source, as it is not cast by a tree or building. It’s possible that it is being cast by clouds, but it is possible that this element signifies the dangers ahead, as we know that the decades after 1682, Europeans and native relations were not always healthy.

But despite the failings of the future, Penn’s treaty was renowned as one of the only treaties to have endured, and was really honored for many, many generations.

The contents of the treaty itself are just so remarkable that I selected several articles that should be read in full here:

Article 1: That all William Penn’s people or Christians, and all the Indians should be brethren, as the children of one father, joined together as with one heart, one head, and one body.

Article 2: That all paths should be open and free to both Christians and Indians.

Article 3: That the Doors of the Christians’ houses should be open to the Indians, and the houses of the Indians open to the Christians, and that they should make each other welcome as their friends.

Article 4: That the Christians should not believe any false rumours or reports of the Indians, nor the Indians believe any such rumours or reports of the Christians, but should first come as brethren to inquire of each other; and that both Christians and Indians, when they have any such false reports of their brethren, they should bury them as in a bottomless pit.

These articles, especially number 4, are important because you always had intelligence operations, especially Jesuitical intelligence operations, manipulating tension between groups in the colonies.

This involved conducting slanders, promoting gossip to various groups in order to induce and increase hostilities between the white men and the natives, or actually manipulating, in a very racist way, certain native groups from Canada, from Quebec, that they would then deploy and conduct massacres using very, very high level MK Ultra brainwashing operations, as those outlined by Cynthia Chung in her recent book, ‘The Shaping of a World Religion: From Jesuits, Freemasons and Anthropologists to the Ghost Dance Religion’.

It was a very nasty operation. And it has been written about over the years how these things were done.

Frederick Schiller also writes about this his 1792 study ‘The Jesuit Government in Paraguay’.[1]

And the fact that this concept was so clearly embedded in William Penn’s treaty is very interesting.

All participants agreed to say: ‘OK, before we react emotionally over some gossip or provocation, which gets us into trouble by unjustly seeking revenge, let’s talk with each other and see if a certain slander is true or false first before reacting.’

And that makes all the difference.

Article five, “That if the Christians heard any ill news that may be to hurt of the Indians or the Indians any such ill news that may be to injury of the Christians, they should acquaint each other with it speedily as true friends and brethren”.

Article six, “That the Indians should do no matter of harm to the Christians nor to their creatures, nor the Christians any harm to the Indians, but each treat the other as brethren first. But as there are wicked people in all nations, if either Indians or Christians should do any harm to each other, complaint should be made of it by the person suffering and the right might be done. And when satisfaction is made, the injury or wrong should be forgot and buried as in a bottomless pit.”

Article eight: “That the Indians should in all things assist the Christians and the Christians assist the Indians against all wicked people that would disturb them.”

And lastly, article Nine: “That both Christians and Indians should acquaint their children with this league and firm chain of friendship made between them. And that it should always be made stronger and stronger and be kept bright and clean without rust or spot between our children and children’s children while the creeks and rivers run and while the sun and moon and stars endure.”

The mode of thinking expressed by this treaty is very emblematic of the Peace of Westphalia, of the Principle of the Benefit of the Other that had only been recently created in 1648—just 40 years before Penn’s Treaty, as the basis of international relations, the creation of the modern sovereign nation state, premised on the Christian concept that the respect of your neighbor was linked to your own self-interest.

With the Westphalia Peace Treaty that ended the Thirty Year War bloodbath that reduced Europe to ashes, a new Christian concept was enshrined into international law that asserted that each nations’ self-interest would now wholly be premised upon the benefit of their neighbor’s welfare and the forgiveness of past transgressions.

Now let’s shift gears just a little bit, and address another problem resolved elegantly by Benjamin West, which is: How do you convey virtue in a painting?

That’s not so easy. You can convey many things in a painting. You can convey emotions. You can convey photo realistic impressions of objects. You can even convey propaganda through the manipulation of emotions.

But how do you convey the type of universal sentiments and universal characteristics that we really should cherish and value in a real democracy?

We will explore this question by reviewing some explosive paintings by Benjamin West that express the highest poetic and philosophical ideals on earth while simultaneously intervening into Universal History.

Benjamin West Arrives in England and makes a Splash

So to get at this, let’s go to 1769, and have a look at an amazing painting that Benjamin West did which really stirred up all of the European nobility.

It was purchased for a thousand pounds by King George III, who really admired it.

It was the departure of Regulus for Carthage.

As the story goes, Benjamin West selected this moment because it expressed a sublime quality of honor and virtue, where a leader and former Consul of the Roman republic named Regulus has been captured in Carthage during the Punic Wars.

While in captivity, Regulus arranged a deal where he would go back to Rome to the safety of his family on the condition that he just argues for Rome’s surrender. However, by the time he arrived at Rome, he has a change of heart and he realizes that he can’t honorably go through this type of argument. He changes gears, and instead encourages the Senate, encourages the people to stand up to Carthage and to fight.

Now, he could choose to stay there, right?

He doesn’t have to go back to Carthage, but he does. He says, ‘well, I disobeyed my word. I will go back and accept whatever repercussions befall me.’

And on the right side of this painting, you have the three Carthaginian ambassadors walking out of Rome and back to their kingdom. You have people begging Regulus to stay back. He’s a very loved military hero, and his people are clearly begging him to stay back.

That’s him right there in the middle, and he’s obviously turning them down.

We have here in one section, a unique anomaly of a woman who is very pensive, and bothered expressing. While everyone else is melting down emotionally, she stands out as the only person who I think expresses a mirror for the audience, as appears to be wrestling in her mind with the difficult philosophical challenge presented by Regulus’ decision.

Is this the right thing to do, or is he being an idiot?

So again, it definitely embodied the type of Roman republican virtue, not dissimilar from the decision made by Socrates and outlined by Plato in his Apologia, Crito and Laws earlier.

Like Socrates who chooses to accept the decision of the Demos of Athens (and whom a teenage Benjamin West featured in his earliest paintings), Regulus is also executed upon his return to Carthage.

Yet despite the fact that he faced torture and death, Regulus decided that it were better for the health of his soul to face that fate than going through a dishonorable life.

It is interesting to me that this lesson is something which still resonated with the king, who increasingly found himself influenced by Benjamin West’s philosophy and lessons.

In 1769, Benjamin West began to spend evenings in philosophical dialogue with the king who was the same age as the painter, and clearly was a young man struggling with ideals that often conflicted with the position he was born into.

West was held back for hours into the evening at Buckingham Palace discussing philosophy, discussing the nature of government and the nature of mankind. And he made his views, his pro-republican views very well known to the king.

And it shows you there’s something about King George III that is not so one dimensional. It’s not so clear cut to have this simplistic dopy evil image of the king that has been passed down to us through pop culture.

Here’s a portrait of King George III in 1779 by Benjamin West featuring the king having just received word of the French-Spanish Armada (featured in the background,) which threatened England with a land invasion during the height of the American revolution.

Now King George III recognized that there was something definitely strong and admirable in Benjamin West which he couldn’t help but admire. And Benjamin West saw there was something definitely noble in the king and even in certain members of the British aristocracy whose patronage and support he needed to remain in good standing. I emphasize this just to get across that the nuance of appreciating the subtleties of players on the stage of history is often lost on modern historians, yet without this appreciation, no truthful appreciation for those who shaped history—for good or for bad (and at some times both at different moments in life)—could occur.

Let’s look at one more painting by West.

What we have here is another painting that was done later on, featuring Cicero discovering the tomb of Archimedes.

I think this is a particularly beautiful story.

I mean, it’s pretty straightforward, but the thing with these historical paintings is that it forces you to go back and study what the artist was studying when he was inspired to select these moments.

What we see in the painting are workers clearing out the weeds, roots and foliage covering up the lost tomb of Archimedes, who had died at the hands of Roman generals.

He had been assassinated about 200 years before this event takes place, and you have people obviously in awe, shocked that here, Cicero, the great Platonist and leader of Rome, actually found it.

Now this is a story that takes place in a dialogue called the Tusculen Disputations written by Cicero in 45 BC. And I had a chance to read some of this. I didn’t finish it yet. But Cicero’s writings are filled with the same metaphysics, philosophy and method of thinking as that expressed earlier by Plato, whom he admired above all philosophers.

In The Tusculen Disputations, Cicero is asking the same questions that shaped the core of Plato’s Phaedo Dialogue featuring Socrates’ last day on earth and a discussion about the soul’s existence, its nature and whether we can know using reason that it is immortal.

And he also incorporates such topics as ‘How do you live a good life? What is a good life?

Is it a life of power and the pursuit of pleasure, where you actually have the power to satisfy your pleasures and get rid of your pains?’

That’s what some tyrants would say is a good life.

In the Tusculen Disputations, Cicero describes his discovery of Archimedes’ tomb. And in it, he says,

“I will present you with an humble and obscure mathematician of the same city, called Archimedes, who lived many years after; whose tomb, overgrown with shrubs and briers, I in my quæstorship discovered, when the Syracusans knew nothing of it, and even denied that there was any such thing remaining; for I remembered some verses, which I had been informed were engraved on his monument, and these set forth that on the top of the tomb there was placed a sphere with a cylinder. When I had carefully examined all the monuments, I observed a small column standing out a little above the briers, with the figure of a sphere and a cylinder upon it; whereupon I immediately said to the Syracusans—for there were some of their principal men with me there—that I imagined that was what I was inquiring for. Several men, being sent in with scythes, cleared the way, and made an opening for us. When we could get at it, and were come near to the front of the pedestal, I found the inscription, though the latter parts of all the verses were effaced almost half away. Thus one of the noblest cities of Greece, and one which at one time likewise had been very celebrated for learning, had known nothing of the monument of its greatest genius, if it had not been discovered to them by a native of Arpinum.

But to return to the subject from which I have been digressing. Who is there in the least degree acquainted with the Muses, that is, with liberal knowledge, or that deals at all in learning, who would not choose to be this mathematician rather than that tyrant?

If we look into their methods of living and their employments, we shall find the mind of the one strengthened and improved with tracing the deductions of reason, amused with his own ingenuity, which is the one most delicious food of the mind; the thoughts of the other engaged in continual murders and injuries, in constant fears by night and by day.”

OK. So that’s just a little segment where he’s getting across… that the life of a true philosopher and a scientist is better lived and more valuable than the life of a tyrant… essentially, the same course of thinking developed by Plato earlier in the Gorgias dialogue.

There is another layer to this.

Just as Benjamin West is a foreigner to Britain who is trying to subtly revive a healthier tradition among a corrupt wayward people, he is also drawing a parallel to the case of Cicero, who was a foreigner to Syracuse.

It is ironic that in history, we find that it often takes a foreigner to go in and actually discover what made a decaying civilization great, since the citizens of that decaying civilization had forgotten their own true heritage, and couldn’t easily see outside of the limits of their own cloudy matrix of lies.

We can now ask: Why was West attracted to this particular story of Cicero, of Archimedes, of Socrates (his first painting), of Regulus and of William Penn?

I think one important element deals with the issue of sovereignty of the individual.

Because you can only be a true sovereign person if you break free of your fear of losing your sensual gratification, your addiction to ego, material comforts and even losing your life.

Unfortunately, most people are just petrified of death, and have no deep relationship with their soul, their conscience that can be made healthier or sicker depending upon the discoveries, and choices and values we choose to defend in this life. These are the types of people who are never going to be able to appreciate, and defend those liberties that are enunciated in the Declaration of Independence or Constitution.

A society devoid of those virtues and trapped by those fears and sensual addictions is a society of subjects incapable of self-government or true Sovereignty.

Benjamin West understood how this is the source of a lot of our corruption.

A lot of people do corrupt things because they’re afraid of death, or they fall for mystical beliefs because they’re afraid of their own immortality. They’re afraid of the implications of, if their soul is immortal, that they should be living their lives in a very different way.

Now let’s contrapose that to the message he’s delivering now in three paintings I’ve selected. Number one is 1777, during the American Revolution.

This is a definite message to King George III.

In our modern world, George III has become well known as the “mad king”.

Movies, plays and novels have been written portraying him as an insane character.

Although it is true that he is the king who went insane and was ultimately taken out of office in 1810 because he lost his marbles, there is something more nuanced to the story.

King George III’s insanity did not come out of nowhere in 1810, but he had several bouts with insanity starting in the early 1780s, and there were signs of it before even that.

Might that be because he, just like Marquis de Lafayette, had two separate, contradictory impulses within him?

The King admired human genius. He admired virtues that were antagonistic to the oligarchical organizing principles of society, which was the organizing system of the British Empire that he had been born into.

To add some additional dimension to the story of the mental breakdown of King George III, and West’s brilliant understanding of universal history, let’s look at another painting by West featuring the story of King Saul and the Witch of Endor.

Do people know the story from the Bible, from the Old Testament of Saul and the Witch of Endor? Anyone? Anybody paid attention in their Bible studies classes in school?

Well, King Saul was about to go to war with the Philistines, but he was very afraid, and he couldn’t figure out what to do.

He was asking such questions as: what do I do? What type of battle plan do I use? Do I go to war even? Maybe I shouldn’t.

He was desperate and wanted to seek the advice of his favorite prophet Samuel, but sadly Samuel had died a few years earlier. So his mind began to toy with the notion of asking a witch or oracle about getting in touch with the soul of Samuel. However, by this time he had already expelled all of the oracles and witches from his kingdom, so he’s in a pickle.

What does he decide to do next?

He goes undercover and creeps into Endor, and finds a witch who was able to help him for money. And she does a ritual and invoked the words of Samuel, which came ringing out from somewhere. And there was smoke and a lightshow. And basically, the forecast was given to him with somebody speaking with Samuel’s voice, saying, ‘yeah, you’re going to go to battle tomorrow. And not only that, but you’re not only going to be defeated, but you’re also going to die.’

Now King Saul was obviously devastated.

He fell down, begging for some different outcome. But the witch of Endor just brushed him off. The next day arrives, and the witch’s prediction comes true.

He goes to war, and gets injured… and actually commits suicide.

What’s the lesson here?

If the battle and his death wasn’t going to happen, his superstitious belief in the forecast literally ensured that he made it all happen, forgetting that he ever had free will or a mind of his own. The forecast had that much power, and is reminiscent of the kind of character we saw crafted by Shakespeare in the figure of Hamlet.

Could Prince Hamlet’s fate have been different had he not chosen to abandon his free will in favor of the stories told to him by the image of his father’s revenge-hungry ghost?

It is also similar in principle to the case of Shakespeare’s Scottish King Macbeth.

In the Tragedy of King Macbeth, we encounter the case of the three witch sisters who very much embody the archetype of the witch of Endor. The three witches give Macbeth this whole forecast, and they plant these seeds into his imagination, which results in Macbeth literally acting out what might not have otherwise happened had his mind not become literally possessed by the idea of murdering his way into power.

Another possible aspect of this story which West is communicating, may be seen in the well known case of occultism embedded throughout the British Imperial elite which West and Franklin understood viscerally. We could see why this republican painter would be making a lot of enemies at this point with the intelligentsia of the Hellfire Club devotees and their heirs.

Let’s now look at another painting by West that continues on this line of thinking.

This is a scene from King Lear which, West painted in 1791.

This is from the famous Act 3, Scene 4 and 5 where King Lear is in a storm, and he stumbles on somebody to whom he had done many wrongs while he was still in a position of power.

This person whom he encounters is now just in a kind of insanity (although he is also partially faking his insanity) by the named of Tom Bedlam. At this point, Tom Bedlam is living in a cave and has been living there for several years and the storm is raging outside of him. King Lear has been betrayed by his wicked daughters, and he’s lost everything.

Lear is suffering the consequences of having lived a life of folly, and self-delusion… and now he is pretty much stuck wandering around aimlessly accompanied by a fool (a jester).

It is a really insightful play and at this moment Lear has the opportunity to go inside the cave and get out of the rain. But he responds to Tom Bedlam’s offer by explaining that the storm in his head is worse than the actual physical storm, so he chose to just remain under the rain.

And he has this brief moment of cogency where he actually says: ‘This is my suffering for the wrongs that I did to my people by not taking care of the poor in my kingdom. And as my impoverished subjects have had to suffer, now I’m suffering too. This is justice befalling me.’

Now West found the story of Lear very valuable, and did many different paintings of King Lear throughout his life. While we can’t know every detail in West’s mind, we can see that this play provides a definite message to anybody who may be a king struggling with insanity amidst an unjust world.

The last painting, the third in the series that I’ve selected here is from a large mural by West painted in 1792 called ‘Pharaoh and Host Lost at Sea’.

These are huge paintings. The theme is visceral of the Egyptian Pharaoh and his host chasing the Jews that have just declared their freedom and have begun crossed the Red Sea. The “moment” conveyed on West’s canvas features the sea collapsing on the Pharaoh’s army.

When considering the world of 1792 and the obsession by leading forces of the British Empire to re-absorb their lost colonies back into the Empire, and considering King George III’s contradictory impulses during this dynamic, West’s deeper meaning should not be missed on anyone.

Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin West and others knew that the true battle of Independence was only beginning even after the British admitted defeat in 1781. In fact, there were top-down policies imposed by the British Empire to ensure that the colonists would not be allowed to have access to manufacturing, that they would be kept impoverished, they would not be allowed to go west beyond the Allegheny Mountains. and that they would just be kept shackled to the east coast. This policy had always been enforced to crush the potential Promethean spirit in the colonists.

So again, the fact that the president of the English Royal Society of Fine Arts who is acting as a shaper of cultural, moral and aesthetical senses within the very heart of the empire is fascinating. The fact that West also trains an entire generation of brilliant young American painters to take on the mission of establishing a uniquely new renaissance American movement with a sensitivity of resolving the European vs Native American AND personal liberty vs General Welfare problems is fascinating.

In 1778, Lord Chatham, who’s also called William Pitt the Elder, dies in Parliament. Actually, not really. The story goes, he dies in Parliament.

In reality, he died 34 days later in his bedroom, but romanticists created an apocryphal story.

Benjamin West decided to immortalize this moment in a famous painting, which doubles as a devastating republican critique of empire. But thanks to his subtlety and the oligarchist inability to recognize irony, the British elite actually like it.

They think he’s doing honor to William Pitt. But if you actually look at what William Pitt was doing when he died, we see a different story emerge.

Pitt had come to parliament specifically to try to fight a bill that was being pushed through by the Duke of Richmond, who on March 23rd called for withdrawal of all British troops from the United States right after getting word that the French were going to come in assisting the American cause.

And the bill was defeated with 56 votes in the House of Lords.

But Chatham on April 5th came out to fight this bill, and to fight these “soft” lords who wanted to let the Americans go free and declare their independence.

And Chatham says:

“My Lords, I rejoice that the grave has not closed upon me; that I am still alive to lift up my voice against the dismemberment of this ancient and most noble monarchy! Pressed down as I am by the hand of infirmity, I am little able to assist my country in this most perilous conjuncture; but, my Lords, while I have sense and memory, I will never consent to deprive the royal offspring of the House of Brunswick, the heirs of the Princess Sophia, of their fairest inheritance. Where is the man that will dare to advise such a measure? My Lords, his Majesty succeeded to an empire as great in extent as its reputation was unsullied. Shall we tarnish the lustre of this nation by an ignominious surrender of its rights and fairest possessions?

Surely, my Lords, this nation is no longer what it was! Shall a people, that seventeen years ago was the terror of the world, now stoop so low as to tell its ancient inveterate enemy, take all we have, only give us peace? It is impossible! ...My Lords, any state is better than despair. Let us at least make one effort; and if we must fall, let us fall like men!”

— Lord Chatham (William Pitt the Elder) April 7, 1778

And then he collapses in a seizure and dies soon thereafter, which one could say is the death of the man. But is it also expressive of the death of the toxic idea that he devoted his life to. As he died, so too did his sick cause.

John Singleton Copley—another American painter born the same year as Benjamin West, who also studied with Benjamin West at the Royal Society of Fine Arts, and who was in that first painting shown above—did another rendition in 1781 of the same “moment” of the death of Pitt.

However, in this case, juxtaposing it with the defeat of the Spanish Armada on the wall by the British 200 years earlier, which I think, again, is very expressive of the past grandeur of the British Empire’s romantic memories dying with this man in this moment of historical change.

The 1588 defeat of the Spanish Armada is known to be the moment that England became the seat of a world maritime empire, replacing the place formerly held by the Spanish Hapsburg Empire. But with the American revolution’s success, the potential was that this would no longer be the case.

As we begin to round out this chapter, let’s take a moment to have a look at the great Benjamin Franklin as seen through the eyes of Benjamin West.

Official narratives tend to infer that very few points of contact exist connecting Franklin with West. As we will see, this was simply false.

We’ll start this last segment with Benjamin West’s 1783 painting called ‘The Peace of Paris’.

Within this painting we can see the American delegation who came to paris to sign the treaty that would officially end America’s war with Great Britain.

We can see John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Lorenz, and the young man is William Temple Franklin who is Ben Franklin’s grandson, whom Ben Franklin was training in statecraft. Now, the reason why this painting is not finished is that the British never really ultimately accepted the fact that they lost the war. The British delegation never showed up for the portrait sitting.

It’s a half finished portrait, which I think is perfect because the revolution itself was never finished, even now, 250 years later, the battle still goes on.

The British oligarchist influence within the USA was never actually extracted, and remained behind to form a powerful fifth column over the next two centuries.

Let’s look at another most famous portrait of Benjamin Franklin, which West painted in 1816 titled, ‘Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky’.

Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky, by Benjamin West 1816

It’s not a very subtle portrait, and really embodies the Promethean principle.

Since his 1752 discoveries of the ‘electric fire from the gods’, Benjamin Franklin had become known as ‘The Prometheus of America’. However in 1816 King George III had gone completely insane and was taken out of power. While West remained the president of the Royal Society, he wasn’t receiving any royal sponsorship or patronage, and found himself quite isolated.

I personally get the feeling that West really has nothing left to lose at this point, and he has decided in his old age, to more explicitly lay out his cards in his heart more openly.

By portraying Ben Franklin who had discovered electricity the way he did and made his proof of principle experiment with the key that was able to capture a charge from a thunderbolt, a new trajectory was created for the development of a promethean civilization.

As noted at the very start of this chapter, Franklin’s discoveries directly gave rise to the advances made on electrical communications by Samuel Morse. Again, this was done with the help of a variety of scientists around the Humboldt brothers, including Carl F. Gauss, Wilhelm Weber, and Ampere.

Benjamin Franklin’s own great grandson Alexander Dallas Bache also figured prominently in this Gottingen-Philadelphia complex of genius during the 19th century.

Professor Pierre Beaudry, who brought so many of the insights featured in this chapter to my attention, also had an interesting hypothesis about an irony found among the five cherubs featured by West in this painting.

It is clear that among some of the cherubs, you have this natural baby-like innocent quality, but you also have these strange adult attributes featured in one of the cherubs.

Is that a mistake? Why would West do this? Is it possible that babies can carry out scientific experiments as the cherubs are doing in this painting?

Perhaps what West is communicating through the use of the visual ironies, is that true scientific discoveries of a Promethean nature can only occur when adults tap into child-like innocence, and wonder that allows us to both play and also explore the unknown with a good heart.

I also appreciated West’s choice to add a native headband to one of the cherubs, indicating the solution to the paradox of harmonizing the interests of European and First Nations cultures.

How can this be done?

It would be impossible without the activation of a spirit of healthy common divine wonder and scientific progress, which is the heritage and right of all people to activate and enjoy.

And just like the school of thought of Ben Franklin, of Ampere, of Weber, that entire way of thinking in the sciences that also was advanced by Samuel Morse and Joseph Henry, just like that needs to be revived in our current age to overcome a lot of these absurd paradoxes that are really holding back science, like the belief in black holes, and dark matter, and multiverses that emerged out of 20th century standard model cosmology and quantum mechanics.

We need to go to something that is more coherent, more natural and more in alignment with how these discoveries were actually made. And the same thing applies for the arts which was understood by these great Promethean figures to be simply another aspect of science and political freedom.

Endnote

[1] Later on, Samuel B Morse even exposes this Jesuitical operation in the America’s in his famous book ‘Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States’ published in 1841 where he described Prince Metternich’s Holy Alliance and it’s deployment of Jesuits throughout the Americas to undo the American revolution when he said “the latter come from the same quarter, in the shape of hundreds of Jesuits and priests; a class of men notorious for their intrigue and political arts, and who have a complete military organization through the United States.”

Badlands Media articles and features represent the opinions of the contributing authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Badlands Media itself.

Matt is the editor-in-chief of The Canadian Patriot Review, Senior Fellow of the American University in Moscow and Director of the Rising Tide Foundation. He has written the four volume Untold History of Canada series, four volume Clash of the Two Americas series, the Revenge of the Mystery Cult Trilogy and Science Unshackled: Restoring Causality to a World in Chaos. He is also co-host of the weekly Breaking History on Badlands Media and host of Pluralia Dialogos (which airs every second Sunday at 11am ET here).

If you enjoyed this contribution to Badlands Media, please consider checking out more of Matthew’s work for free on Substack.

Badlands Media will always put out our content for free, but you can support us by becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter. Help our collective of citizen journalists take back the narrative from the MSM.

No one writes at this level for money, because there's no money in it. Outstanding expose but... who is the target audience for a piece like this?? I'm not saying this to be a dick, I'm just genuinely curious....

Most fascinating, Mr. Ehret. I just finished watching Frontier and now onto watching Washington's Spies. As you can see I am not a television snob but enjoy the historial drama as I have always been interested in the history of our founding. IMHO neither of the series I mentioned are "great" but I find it enjoyable to watch and see how your wonderful writing adds further depth and insight. TY for this excellent piece.