'Oppenheimer' & The Central Narrative

Nolan Refreshes Our Collective Memory & Foreshadows Changes in the War of Stories

Badlands Media will always put out our content for free, but you can support us by becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter. Help our collective of citizen journalists take back the narrative from the MSM. We are the news now.

Oppenheimer, the three-hour Christopher Nolan biopic about the Manhattan Project and nuclear arms race, hit theaters last week. In a nod to Idiocracy, Greta Gerwig’s Barbie also released last week, and the two titles gave studio titans some much needed box office success.

From AP News:

“Warner Bros.’ ‘Barbie’ claimed the top spot with a massive $155 million in ticket sales from North American theaters from 4,243 locations, surpassing ‘The Super Mario Bros. Movie’ (as well as every Marvel movie this year) as the biggest opening of the year and breaking the first weekend record for a film directed by a woman. Universal’s ‘Oppenheimer’ also soared past expectations, taking in $80.5 million from 3,610 theaters in the U.S. and Canada, marking Nolan’s biggest non-Batman debut and one of the best-ever starts for an R-rated biographical drama.”

Did you catch that? Oppenheimer did just a little more than half (52%) as well as Barbie.

Our culture is broken.

A Historical Retelling with Purpose-Filled Themes

The film follows J. Robert Oppenheimer from his time as a young theoretical physicist, learning from the greatest contemporary minds across Europe before returning to the US to create a competitive theoretical physics capability in US academia. Once Cockcroft and Walton split the atom in 1932, the film depicts an almost instantaneous shift in the science from research to development. That is, the greatest scientific minds of the time moved, seemingly overnight, from researching the universe to developing the atomic bomb.

In an ambitious attempt to rewrite history and refresh the collective memory about nuclear fear porn, Oppenheimer sacrifices entertainment value in favor of narrative value – and it shows.

This was the most boring Christopher Nolan film I’ve ever seen. The approach to storytelling felt more like Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991) – which was also insufferable – rather than the more thrilling, mind bending storytelling we’ve come to expect from Nolan.

There are glimpses of the director in the use of sound, and in the more psychological moments when Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) is stuck inside his own mind. The infamous Los Alamos nuclear test is beautifully shot and provides updated visuals of the ‘formiddable power’ of nuclear weapons. If you watched the Baseless Conspiracies episode on Nuclear fear porn during the 1930s, you know how desperately those visuals needed an upgrade. If you missed that episode, it's must watch companion viewing for Oppenheimer.

Despite its failings in entertainment value, the film still held my attention largely due to Nolan’s heavy-lifting for the central narrative. There are several themes throughout the film that demand critical examination, so let’s jump in.

Communists are Just Misunderstood

J. Robert Oppenheimer’s communist associations are historically documented, and Nolan leans in, telling the story of a non-committal communist sympathizer who is, at least in part, using the central planning ideology to get laid.

In one of the first scenes where he is attending a communist meeting with his brother, Oppenheimer is introduced as a skeptic of communism to his future mistress, Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). Tatlock locks Oppenheimer in a sultry gaze and says something along the lines of, ‘That means he doesn’t understand it.’

Tatlock is portrayed in the film as Oppenheimer’s troubled mistress, but, according to the historical record, she was a promising physicist in her own right.

Trained at Stanford, Tatlock was an active member of the Bay Area Communist Party and has been described as Oppenheimer’s “truest love.” Their relationship, as well as Oppenheimer’s ongoing flirtation with communism and union politics, threatened his career and led, ultimately, to the Atomic Energy Commission stripping him of his security clearance in, according to the film, a premeditated public humiliation ritual. The film and the historical record paint this controversy as the reason Tatlock took her own life at the age of 29.

Throughout the three hours, communism is presented as a misunderstood ideology. Most of the scientists and intellectuals are portrayed as either practicing communists or noncommittal sympathizers. The smartest people in Nolan’s version of the nuclear arms race are the communists, and the director contrasts their socially conscious and pragmatic positions against the military war machine and ambitions of corrupted politicians.

Robert Downey, Jr. is the face of the latter group as Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss, a Virginia-born businessman, philanthropist, and naval officer who served two terms on the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)—the second as its chairman. Strauss is painted in both the film and the historical record as a villain.

This subtle theme sets up an alternate telling of history where we just might have saved Hiroshima and Nagasaki and prevented the nuclear arms race, as well as the subsequent Cold War, if only American authorities had listened to the communists, shared information with the Soviets, and paused future development efforts to allow the ethics of the atomic bomb to be thoroughly debated.

Nuclear Weapons are the Destroyer of Worlds

The most stunning visuals in the film are those of the bomb, and its conception, development and detonation in the New Mexico desert.

As the scientists test their theories in Los Alamos, Nolan takes the audience on a journey through Oppenheimer’s mind with mostly indecipherable, but beautiful, visuals intended to depict the physicist’s contemplation of particle theory, string theory, and quantum mechanics.

The most controversial moment comes as Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists are debating what will happen upon detonation, and they become concerned that they might literally destroy the world.

From ScienceFocus.com:

“There is a scene in Christopher Nolan’s new film Oppenheimer (a biopic of J Robert Oppenheimer, the man who invented the nuclear bomb) in which Leslie Groves, an army engineer played by Matt Damon, worries about destroying the world. This is just before the Trinity test, the first-ever detonation of an atomic bomb, and Oppenheimer says he’s confident that the chances of annihilating all life on Earth are near zero. ‘Near zero?’ splutters Groves. ‘Zero would be nice!’

In reality, Groves’s concerns were those of Manhattan Project physicist Edward Teller. According to Dr Steven Biegalski, Chair of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology, Teller was worried that the heat of the explosion ‘would cause the hydrogen in the atmosphere to undergo fusion, setting off a catastrophic chain reaction that would continue around the globe and destroy Earth.’”

This theme – that scientists are playing with highly dangerous capabilities they don’t fully understand – is prominent from the very beginning of the film, which frames Oppenheimer as a modern Prometheus in the opening scene:

“Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man. For this, he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity.”

This continues throughout the film in Oppenheimer’s reflective moments and debates with his fellow scientists, and Nolan puts a fine point on the theme with Oppenheimer quoting the Hindu Bhagavad Gita, “Now I Am Become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

A secondary—and I would argue, unintentional—theme that results from Nolan’s telling is the fallibility of science. The film attempts to paint the scientists in a sympathetic light, and it largely succeeds; but in doing so, there is a spotlight on how much of science is untested theory and how limited is man’s understanding of the universe.

The smartest minds in the world have just split the atom – a monumental scientific achievement – and their hubris moves them immediately into military application. As a result, scientists in the film are constantly admitting that they don’t know. (How refreshing, considering that our modern scientists claim to know everything.) But these admissions become instantly unsympathetic as the scientists continue to press on – not in research or the pursuit of truth, but in developing capabilities they openly fear will destroy the world.

From the storytelling to the visuals to the embedded themes, Nolan is reminding the audience that nuclear weapons are an extinction-level capability; that is, the people who control nuclear weapons have the power to destroy the world.

In a glowing review that claims Nolan’s film “rights historical wrongs” for Oppenheimer, The Nation writes:

“...the viewing public will decide whether it expresses the tremendous significance of the Oppenheimer case for American democracy—and for humanity’s struggle to contain the terrifying risks and catastrophic effects of nuclear weapons.”

Be very afraid.

Global Governance is the Only Solution

The final theme I want to discuss here builds upon the first two. As Oppenheimer internally struggles with creating such a dangerous capability, he begins to express his concerns to the political and military figures around him. He brings up sharing the science with the Soviets and engaging the United Nations in an oversight capacity.

The film, naturally, highlights the nationalistic rejection, and tees up the answer in hindsight: Globalism.

Indeed, that was intentional.

The film was inspired American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. Sherwin passed away in 2021, but Bird consulted on Nolan’s film and said he hopes it will start a societal conversation, as if we needed more evidence that Oppenheimer prioritizes narrative value over entertainment value.

“I have hopes it will actually stimulate a national, even global conversation about the issues that Oppenheimer was desperate to speak out about,” Bird said during a mid-May seminar at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, where Oppenheimer served as director from 1947 to 1966. “About how to live in the atomic age, how to live with the bomb and about McCarthyism. What it means to be a patriot, and what is the role for a scientist in a society drenched with technology and science to speak out about public issues.” — Union of Concerned Scientists. The Equation. “Ask a Scientist: Scientists and Arms Control from Oppenheimer to Today.” (July 13, 2023)

Nolan, Bird, and the film are nudging us to accept that globalism is the only answer to the ‘growing’ nuclear threat, and most of the reviews and other coverage of Oppenheimer touch on the film’s importance in helping the public understand the real threat of Russia’s nuclear capabilities and the threat it poses in their ongoing conflict with Ukraine.

This conveniently aligns with nearly every other societal domain.

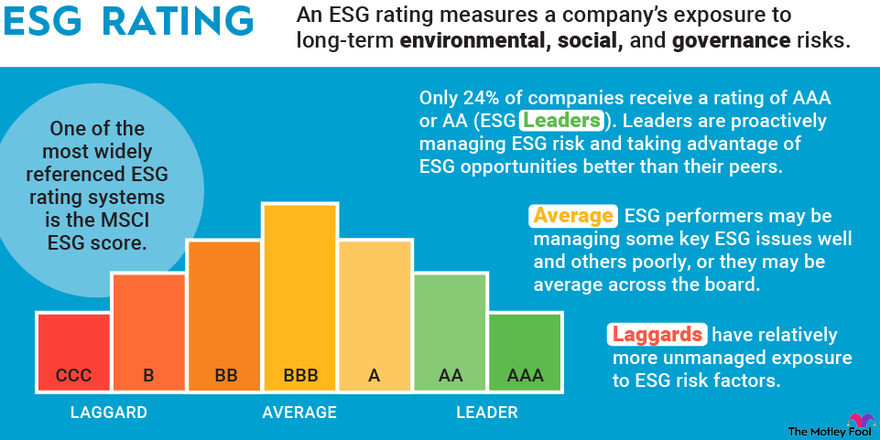

Our institutions are currently painting globalism as the answer to all societal problems, from climate change and migration to global health and pandemic response to technology innovation and artificial intelligence. Add to that the ongoing impacts of corporate Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) initiatives, and the global corporate communist agenda is on full display for anyone willing to look.

Governance is about decision rights.

Global governance is about global decision rights.

This raises a conflict between national and global decision rights that must be dealt with through the Great Reset to the New World Order.

National interests and autonomy are a barrier to achieving global governance — global decision rights. Nolan’s Oppenheimer moves the needle in painting the nuclear threat as an imperative worth sacrificing national and individual liberty.

But it’s not about nuclear weapons at all.

The Power to Destroy Worlds

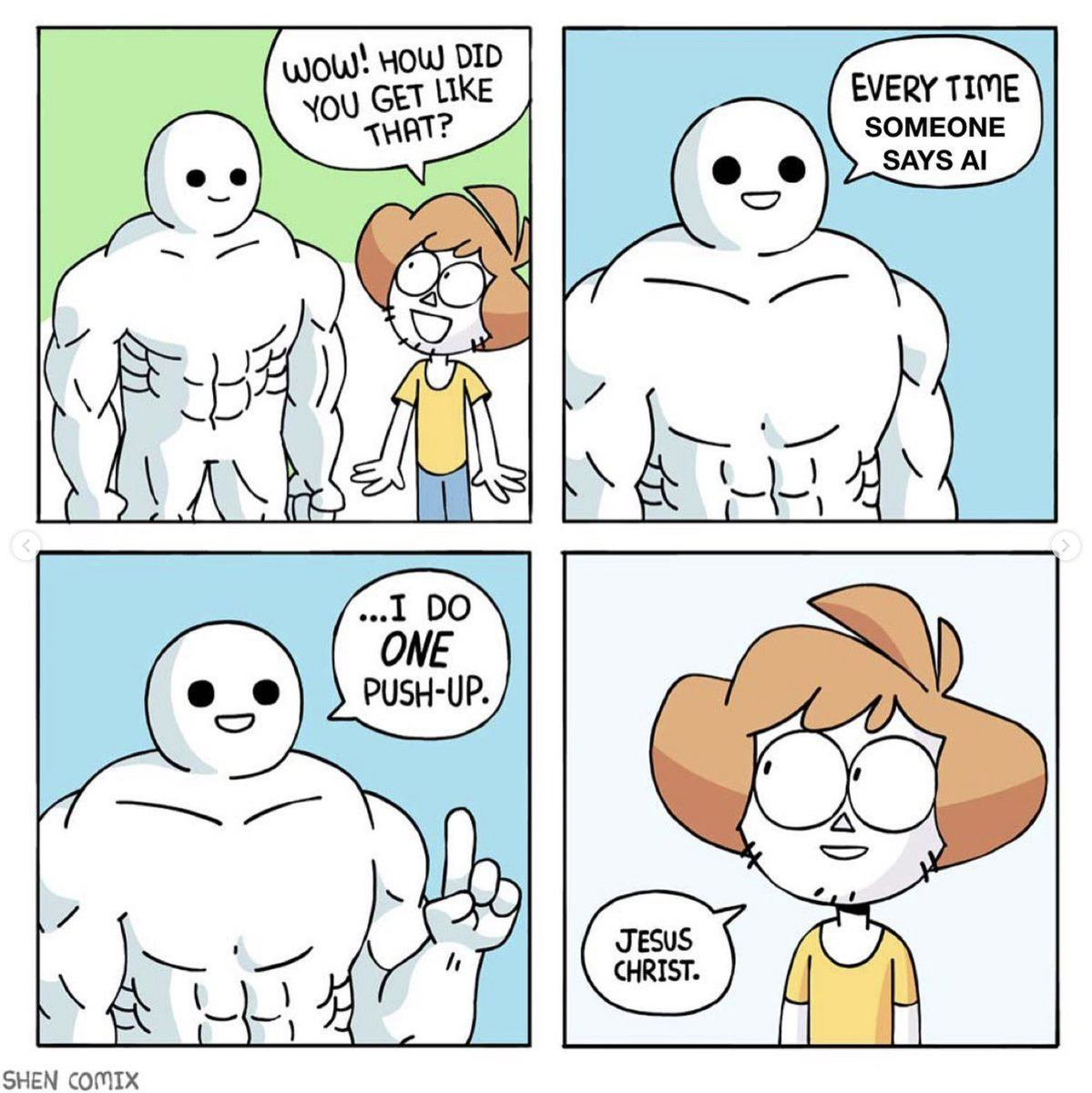

In preparing for last week’s Raising a Nation, I found The Saturday Evening Post’s latest article about Artificial Intelligence. It’s a normie-targeted explanation of the coming AI apocalypse, and I sent it to Kate as a potential discussion topic.

She sent me back this:

The talk of AI is pervasive, and AI researchers have certainly succeeded in setting up a ‘global conversation’ about the looming threat. But what fascinates me most about the AI discussion are the talking points, and the precision and discipline with which the regime’s experts deliver these talking points.

As I wrote in my last piece, Artificial Intelligence: Hysteria vs. Reason, “In an open letter published March 22, 2023, many in the AI research community, including Tristan Harris, Ava Raskin, Noah Yuval Harari, and Elon Musk, call ‘on all AI labs to immediately pause for at least six months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4.’ Gawdat’s ‘three inevitables’ come to mind here: (1) AI is happening. (2) AI is becoming way smarter than us Humans. (3) Really bad things will happen.”

The primary AI metaphor used by the regime to drive hysteria and push for global governance is the nuclear arms race.

Remember, we just might have saved Hiroshima and Nagasaki and prevented the nuclear arms race, as well as the subsequent Cold War, if only the American authorities had listened to the (global corporate) communists, shared information instead of keeping national secrets, and paused future development efforts to allow the ethics to be thoroughly debated.

This is exactly what AI researchers are pushing for now.

The threat of nuclear winter doesn’t hold the weight it did in the mid 1900s and, while it led to unprecedented societal transformation in the last century, it’s not likely to force Americans to yield their little remaining liberty for security.

Nolan’s film seeks to reduce American apathy about nuclear weapons, but only in an effort to strengthen its use as a metaphor. Oppenheimer refreshes the public memory about the race to develop world-ending capabilities, with an all-star cast and modernized mushroom cloud imagery, at the precise moment the global regime needs the public to remember.

What luck!

The comparison of AI to nukes becomes much more vivid and accessible — and terrifying — to 2023 Americans with the historical refresh of Nolan’s film. In fact, the three themes so prevalent in the film directly support the AI narrative:

Listen to the communists — They’re just misunderstood and comprise some of the smartest minds in the world.

AI, like nuclear weapons, is a world-destroying capability — ‘AI is an arms race.’ ‘Nukes can’t create more nukes, but AIs can create more AIs.’

Global governance is the only answer — National interests are barriers to global safety and decision rights must be globalized for AI.

It’s exactly the same objective, themes, and talking points – and it’s not a coincidence. The nuclear narrative is the same narrative they are using with AI:

‘Fear us and submit, for we have the power to destroy you.”’

As I said at the top, Nolan’s Oppenheimer sacrifices entertainment value in favor of narrative value. It’s too long. It’s surprisingly boring. It rewrites history, deifies science, and advocates for globalism.

But it’s successful at reminding the public about the nuclear arms race — and its alleged devastation — at the precise moment the regime is making the comparison and calling to sacrifice national sovereignty in favor of global decision rights.

Will it work?

Badlands Media articles and features represent the opinions of the contributing authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Badlands Media itself.

Ashe in America hosts Culture of Change on Badlands Media, Sundays at 6PM ET. If you enjoyed this contribution to Badlands Media, please consider checking out more of her work for free at Ashe in America.

Communism and world government are the same:

Christianity without God.

So they will fail.

Very very interesting analysis! My grandfather studied under Oppenheimer and turned down the chance to be part of the project for ethical reasons. Bravo.