Badlands Media will always put out our content for free, but you can support us by becoming a paid subscriber to this newsletter. Help our collective of citizen journalists take back the narrative from the MSM. We are the news now.

New to the Patriot Chronicles? Start here.

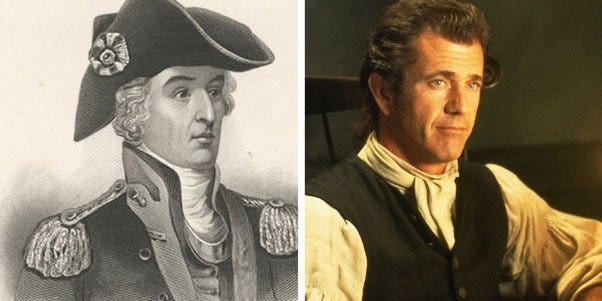

Did you know? Mel Gibson’s film, The Patriot, was based on real people and events?

In fact, it was originally written to be a biographical film, with the explicit, “THE FOLLOWING IS BASED ON A TRUE STORY” wording at its beginning—as revealed by a leaked 1998 screenplay— but after the film producers were threatened by outraged British scholars, spouting lies about the film’s subject, threatening to destroy its credibility in the public square before it was even released, the producers opted to change the names of the entire cast and market it as pure historical fiction. It was not fiction—though artistic license was used on select scenes. Cancel culture took this from us.

(They attacked it with false claims, anyway. Standing invitation to Christopher Hibbert to debate me on this topic, on livestream. He won’t, because these claims are even bigger lies than the “safe and effective” vaccine scam. Note that of the four books I’ve cited, two are written by primary sources—one who served under Marion, another who interviewed him— and a third is by a secondary source who interviewed Revolutionary War vets. Come at me, bro.)

Today, we take it back.

Prologue

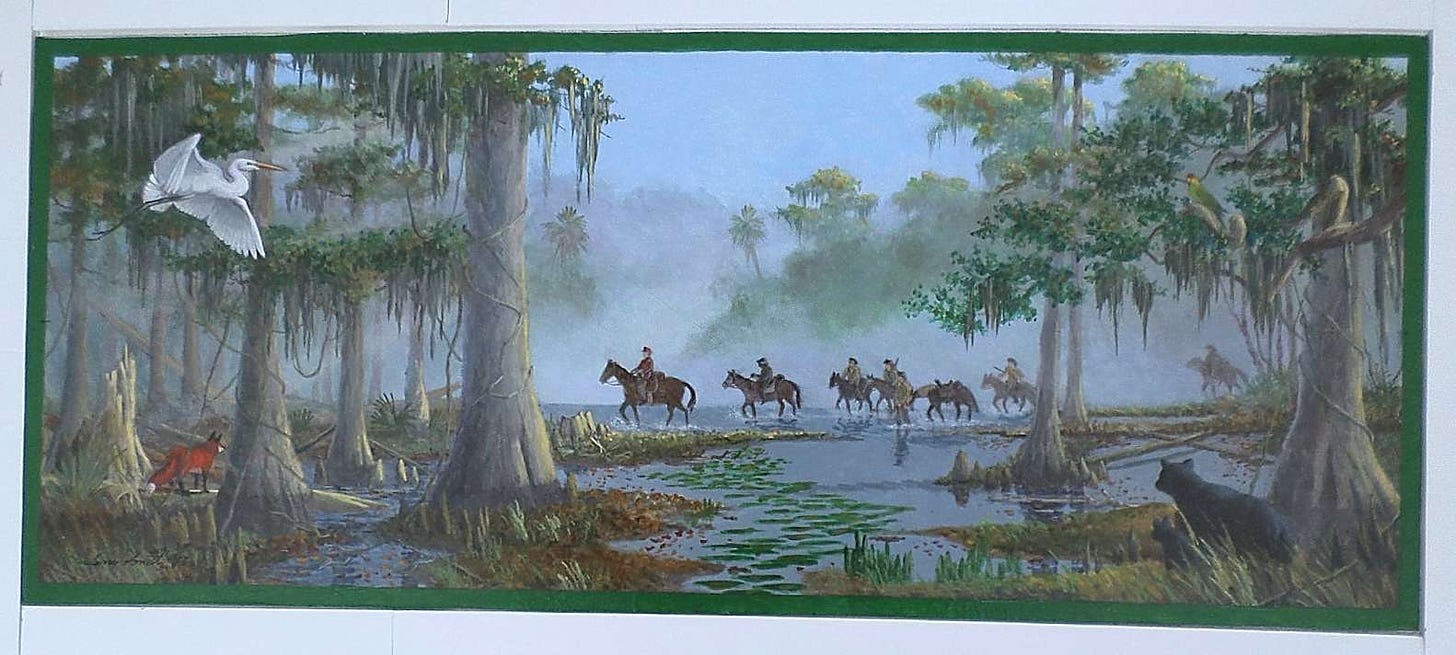

Francis Marion was the American Robin Hood. A former Continental officer, left alone, deep behind enemy lines, after the Continental Army and other militia leaders had been driven out of South Carolina entirely. He was a man on an island—both figuratively and literally— called Snow’s Island, which was a 3-mile stretch of dry land buried deep within the swamps at the confluence of the Pee Dee River and various creeks.

Conventional wisdom at the time assumed that malaria and other diseases spawned from the festering morasses of lowland swamps, such as those that dominated much of eastern South Carolina. For that reason, the marshlands were uninhabited, making it the perfect base of operations for a vigilante.

Snow’s Island would serve as Marion’s Sherwood Forest, with bulwarks made of fallen trees, ramparts of moss-covered rock, and a moat of endless muck, guarded by the legends of sleepless rifles and cunning swamp men who moved like the Cherokee of the Appalachia. It was a fortress as impregnable as any castle in Europe.

And Marion had others just like it, scattered across the region. A classic guerilla warrior, he was constantly on the move to keep his secrets a myth, and the actual strength of his numbers, a mystery. For all the other glaring deficiencies of his brood, his operational security was tight as a drum.

After the British invaded Charleston in the spring of 1780, they took the city with an entire Continental Army trapped inside. A few months, another Continental Army that had marched south to liberate Charleston was decimated and capture, at the Battle of Camden.

With all colonial and militia forces driven from the colony of South Carolina, nothing appeared to stand between the British and George Washington in Virginia. It seemed that this American Dream was about to be crushed in the jaws of the Lion.

Before long, the world’s global empire found itself bogged down in the Carolina swamps, haunted by a ghost. Despite achieving total control of the region, capturing two continental armies and thousands of militia volunteers, they were unable to move supplies or even communicate between commanders, all because of one man— the apex predator of the marsh.

For these reasons, Francis Marion is recognized not only as the father of modern guerilla warfare, but also the progenitor of US Army Special Forces, specifically the 75th Ranger Regiment and the Green Berets.

A Merry Band of Misfits

July 25th, 1780. General Gates’ Camp near Buffalo Ford, North Carolina.

“They were a motley-looking bunch, the twenty or so militia volunteers who rode on horseback that day into the camp of General Horatio Gates, the newly appointed commander of the American Continental Army in the South. Some were white, some were black, and among them was a Catawba Indian or two, enemies of the British and Cherokees. A few of the soldiers were barely in their teens. One of Gates’s officers, noting the “wretchedness of their attire,” described the newcomers’ appearance as “so burlesque” that the Continentals had to restrain themselves from laughing at them.” (Oller 3)

At the head of this host was a small man with fire in his eyes. The Continental Army uniform he wore—despite its tattered and crumpled condition—kept the laughter of the observing soldiers at bay. Though he walked with a pronounced limp, he moved with the quickness.

General Gates was the epitome of a British officer: English-born, school-trained at a military academy in the art of open-field warfare with set pieces, a former major in the British army, and a devoted observer of the European rules of engagement. Any deviation from these conventions was an affront to his notions of civilized society. And yet, here he was, commanding an army of farmers and peasants in open rebellion against the paragon of pomp and circumstance— the British Empire.

To Gates, the concept of guerilla warfare was not only an inferior form of combat, but indicative of an inferior intelligence. It was the blunt blade of undisciplined savages.

Our Hero

Born in 1732 (same year as George Washington) with one leg shorter than the other, not much was expected of Francis Marion. In the wilderness of 18th century South Carolina, such a birth defect could very well have been a death sentence. But Marion was an ardent man. He learned to move with the quickness, and despite a small frame, thrive as both warrior and farmer.

His first great test came at the age of 15. Seeking a life on the sea, he became a deck hand on a small merchant vessel in the Caribbean. On his first voyage, a whale attacked the ship, sinking it with such speed that the crew didn’t have time to grab food or water before escaping in the row boat. After three days adrift, they were forced to eat their little cabin dog’s raw flesh, who had emerged from the wreckage and swam to them. (Ghost’s jest that “a dog makes a fine meal,” was a nod to this anecdote.)

They preserved its blood, which they drank in lieu of water, buying them another week of life. The captain and first mate soon lost their minds, diving into the sea from madness. The other men expired from exposure, and the flock of seagulls feasting on their corpses drew the attention of a passing vessel.

Incredulous, they pulled the small boy out from the pile of decay. He had used their bodies to shield himself from the sun and ravenous birds. Smart lad.

Francis Marion was a survivor. When all hope seemed lost, he scraped the bottom of the barrel and found resolve.

He was exactly what the American Revolutionaries needed in 1780, as South Carolina burned, neighbor massacred neighbor, and all American military forces had been driven out of state, captured, or destroyed.

The British had spent five years in a virtual stalemate with George Washington up north. Both sides had major victories, and defeats, with little ground to show for it, and a new plan was crafted to subdue the peasant rebellion.

Knowing that many of the families who inhabited the southern colonies were of noble birth, the British trusted that these bloodlines would remain loyal to their ancestral homeland, if called upon. So they devised a devious plot: Invade the colony of South Carolina— where these loyalties ran the deepest— and call the bannermen of the New World to rise up and subdue the peasant insurrection.

However, here there was another faction of bannermen from the Old World, who inhabited the lowlands between the Santee and Pee Dee Rivers: the Scotch-Irish: the sworn enemy of the English Crown.

The rivalry between these two groups goes back over a thousand years, similar in timescale and bloodshed to the conflict between the Shia and Sunni Muslims of Arabia.

The true test of this so-called “social experiment,” as intellectuals like Benjamin Franklin described the rebellion, would be whether a French Huguenot like Francis Marion could rouse and lead an army of lowborn Scotch-Irish against the greatest global empire of all time.

Could this eclectic group of longtime rivals, which was more diverse than just the Huguenots and Scotch-Irish, put aside their petty differences, and forge themselves into a weapon capable of killing empires?

Could they become something greater than the sum of their individual parts?

It’s unclear how much time Francis Marion spent ruminating on this question. He was likely too busy trying to survive. After spending 5 years as a commissioned officer in the Continental Army, working up the ranks through hard drilling of the men and diligent construction of fortifications along the coast in anticipation that the British would return the war to the southern theater, Marion now found himself at a cocktail party in downtown Charleston, surrounded by flamboyant officers in powdered wigs and tights.

It was the spring of 1780, and rumor had it that Sir Henry Clinton had landed an enormous army 30 miles south of Charleston, in the direction of Savannah— the south’s only deep-water port— which the British had taken just 6 months before.

Nobody at the party seemed concerned. They were all consumed in the moment; in the gratification of the here and now. And yet, a conquering evil was on the horizon, on its way to crush their joy and strip them of their prosperity. How could they not care?

When the party host locked the doors— a common practice of the day— Marion decided that perhaps the Continental Army was not the military outfit he thought it was. He excused himself upstairs to use the privy, found an unlocked window, and jumped.

The fall severely broke his ankle, but it was a fitting metaphor for the pivotal choice he had just made.

With the help of his longtime friend and confidante, Buddy— a former slave who Marion had freed— Marion hobbled out of town, just as the British arrived and took control. The two friends would spend the next few months on the run in the back-country as they evaded capture and sought out hardened militants who shared their firebrand worldview.

They found them in pubs and taverns and churches and rice fields. Most of them were Scotch-Irish veterans of the French and Indian War. Men who had fought the Cherokee on the frontier, and had suffered, firsthand, the art of guerilla warfare.

There were also the half-breed Catawba Indians. The Catawba had helped the colonists fight the Cherokee, and some intermarried. Their children walked both worlds, but sadly, were never fully accepted by either one. Perhaps this social experiment—this revolution— offered a new beginning?

Freeman— the term used for former slaves— were also drawn to Marion’s call. As were highborn Scotsmen, lowborn Englishmen, Irishmen, Huguenots, Pollacks, and all manner of outcasts and go-betweens. In time, Marion’s Merry Men would rival any half-forgotten legend of Robin Hood, in both size and deed.

Being a seasoned drill-instructor, Marion was quick to train them up in the art of warfare. He taught them to ride and shoot from horseback, both of which he did with proficiency, but also to fight with a saber—since most of his men didn’t carry more than a few rounds of ammunition at a given time, and using the lightweight Kentucky long rifle, they could not fix bayonet.

Sabers were harder to come by, so Marion foraged for discarded mill-saws, and recruited blacksmiths to reforge them in the forest. “Rag-tag” and “misfits” were often the pejoratives used to describe the group’s appearance, and they weren’t unfounded. They were constantly foraging for clothing, as many of them were without shoes.

But the birth of every hero is a challenge to the universe to spawn a villain of equal pedigree. In the case of Francis Marion, and the American Rebellion, God did not disappoint.

Our Villain

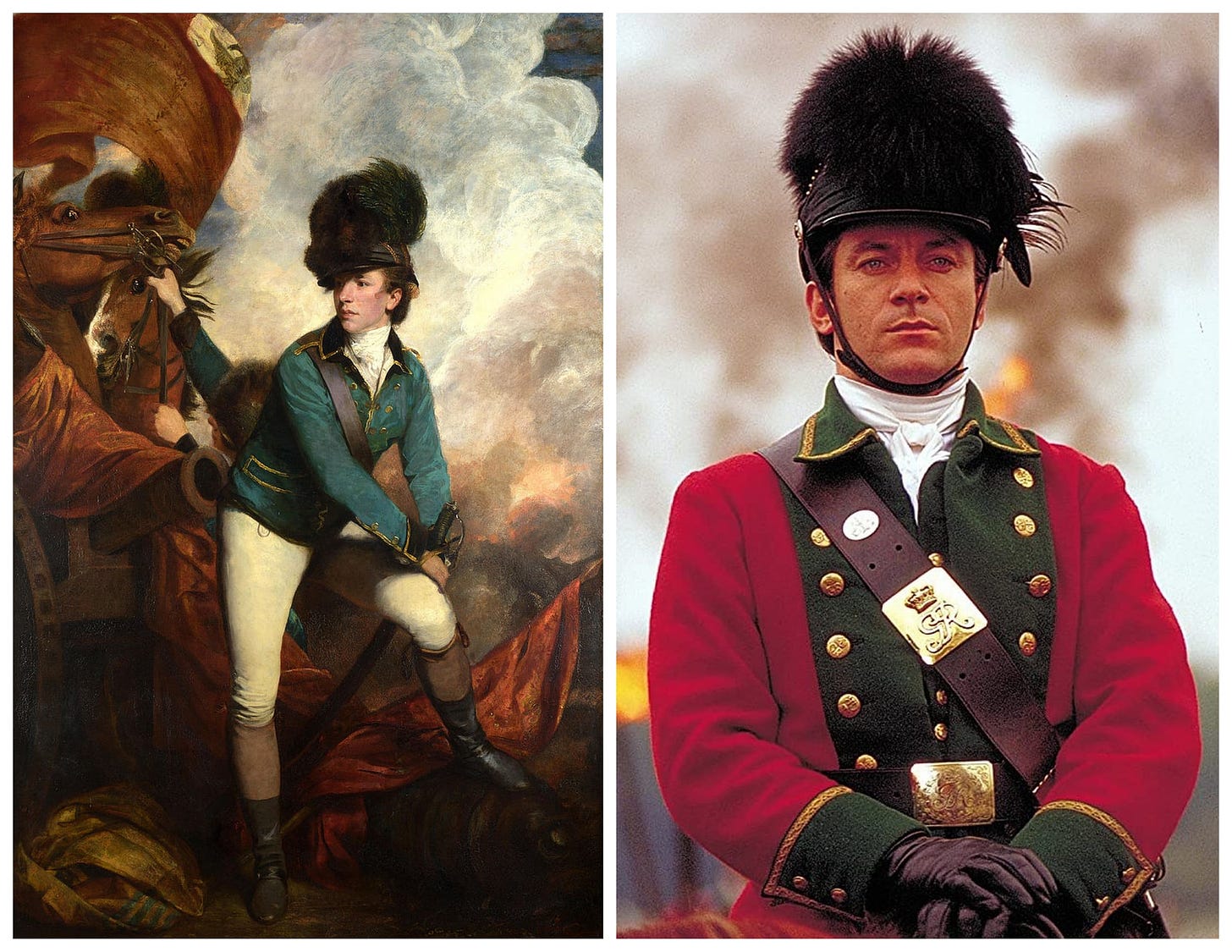

Banastre Tarleton— GOAT villain name— was like something cooked up in the mind of a great fiction writer.

A highborn son of an industrious money-lender and slave-trader, yet notoriously lazy and incompetent in commerce. He was good-looking and allegedly charming—bedding the famous mistress of the future King George IV, and then her daughter—but also a gifted athlete with a sharp tongue for wit.

After his three brothers rejected his desire to join the family business— they were concerned he would follow in their late father’s footsteps, and squander the profits. Tarleton took his 5,000 pound inheritance and blew most of it on women, gambling and drink. The last 800 pounds he used to purchase the lowest-level calvary commission in the British Army, a common practice for the sons of affluence.

Tarleton came to America seeking gold and glory through conquest. To him, the colonists were nothing more than an opponent on a chessboard to be vanquished, and he had developed a habit for bending the rules, as long as the results he delivered satisfied his superiors.

Upon landing in New York, Tarleton’s ascension through the ranks was meteori—all due to merit, not nepotism. He was a ruthless and cunning warrior. He had a passion for violence, and warfare was the perfect vehicle for him to scratch his more sadistic itches.

Unlike Europe, which has open fields well-suited for large-scale mounted warfare, America’s east coast is a more challenging topography. George Washington actually never developed a taste for cavalry, which is why the Continental Army went quite some time without any horseback troops. Again, Tarleton’s cunning ingenuity and ruthless disposition served him well, empowering him to exploit opportunity.

Leading a scouting party in New Jersey in December 1776, he came upon a farmhouse that had been occupied by General Charles Lee. Lee was caught in his pajamas, without a guard posted—a demonstration of his ineptitude. Ban threatened to burn down the house with everybody inside, unless Lee surrendered, which he did.

(Unbeknownst to Tarleton, Lee was a hated rival of George Washington, and had plans in place to usurp him as Commander of the Continental Army. Had Lee’s coup succeeded, Washington’s bold tactics at Trenton one year later would have never transpired, and the Revolution could very well have ended in failure just six months after the signing of the Declaration. From this perspective, one could argue that this act alone made Tarleton a great patriot; perhaps he deserves his own chapter.)

Clinton quickly made Tarleton a Luitenant Colonel, with a 600-man unit to make his own. In lieu of the iconic redcoat, he had them don green riding jackets, so his dragoons would be unmistakable to all in the field. (This backfired, given their misconduct.) He also adopted a fanciful helmet with a large plume—a throwback to paladins of the 13th century. What sweet irony, the notion of chivalry.

The helmet was later adopted by all British calvary troops. The green jacket was not. However, Tarleton became known among the British as the “Green Dragoon.”

The Americans developed a very different name for him.

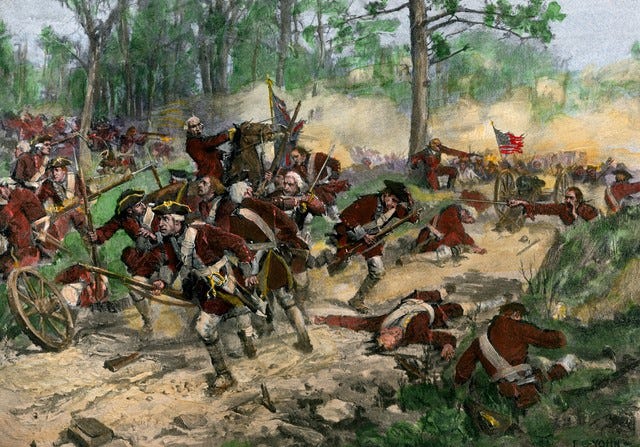

Ban The Butcher

When his siege of Charleston began, Clinton unleashed Tarleton, ordering him to cut off all escape routes from the city, and ride down any fleeing military units.

One of these units was a group of Virginia militia, who had just marched down from North Carolina to reinforce Charleston. They encountered a group of Continental dragoons riding north, escorting South Carolina Governor John Rutledge, who wanted to raise more militia as he retreated from the state.

They turned north, together, heading for Charlotte. The dragoons and Virginia militiamen made camp in Waxhaw, SC, instructing the governor to ride on to safer ground.

This was where Tarleton, riding full tilt, came upon them.

It was a short battle. As casualties mounted among the inexperienced militia; their leader told them throw down their arms, as he raised the white flag. Multiple observers confirm that after the white flag had been raised, Tarleton drew his saber and led a charge through the ranks, cutting them to pieces. Tarleton would later claim that his horse was shot out from under him, and fearing that their beloved leader had fallen, his men retaliated out of revenge. (Still a war crime.)

113 killed, 150 severely wounded, and another 200 taken prisoner, in a matter of minutes.

The story became widespread, and the bloodlust known as “Tarleton’s Quarter.”

It was hardly the first or last time Tarleton would demonstrate such reckless hate toward the colonists.

With Marion frustrating all British logistics throughout South Carolina, it did not take long for Lord Cornwallis (now in command) to summon his dog and sic him on the Patriot. The Butcher had spent the past six months thrashing every senior commander in his path, and had no reason to think this would be any different.

Cornwallis, meanwhile, had issued orders to increase the severity of treatment of suspected patriot sympathizers. Anybody found with any firearms on their property would have their home burned. He was frustrated that he was still in South Carolina, when he should have already been in North Carolina.

Entirely due to Francis Marion.

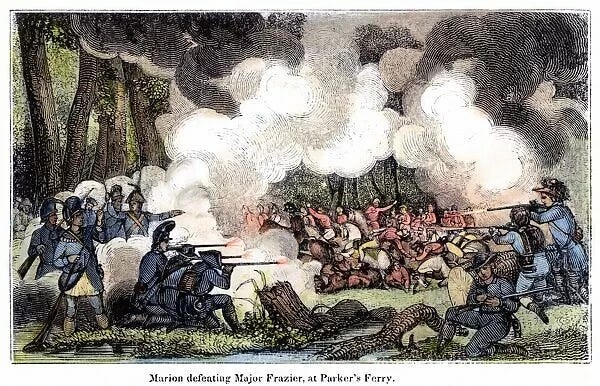

“The Swamp Fox” — The Legend is Born

The first tête-à-tête between Tartleton and Marion was a true cat-and-mouse affair.

Marion laid an ambush at Nelson’s Ferry. Sensing danger, Tarleton pulled back, and dispersed rumors (psyop warfare) that he was retreating back to Camden, ordering his scouts to leave “signs of sudden fear,” such as campfires burning with food still cooking. The Butcher then went to the home of a revered [deceased] patriot—Brigadier General Richard Richardson—and pretended to burn it by lighting a cart of hay on fire. It was an invitation to attack a retreating force at night— Marion’s calling card.

In reality, Ban had wheeled cannons into place, and hid in the woods with 400 men, like a Francis Marion wannabe.

Marion almost took the bait. As he moved his men into position, he ran into Richardson’s son. The son, a 39-year-old militia major and former POW from Charleston, risked his life to slip past Tarleton and warn Marion. (The level of commitment Marion inspired in the men around him.) Marion pulled his men back, and they rode deep into the swamp at Jack’s Creek—considered impenetrable—to spend the night.

The next morning, Tarleton caught wind of Marion’s movement, and spent the next 7 hours in full gallop pursuing him. Finally, in frustration, he relinquished:

“Come my boys! Let us go back, and we will soon find the Gamecock [Thomas Sumter]. As for this damned Swamp Fox, the devil himself could not catch him!”

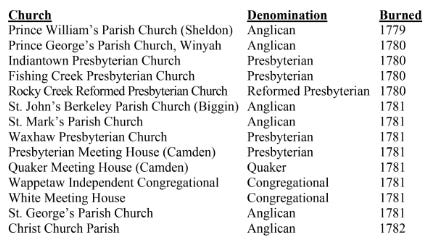

Tarleton returned to Richardson’s plantation, and began beating his widow mercilessly, demanding that she reveal the location of Marion’s men, or their families. He burned her home— for real, this time— but also burned her cattle, burned her cornfields, and took her horses.

Tarleton then went on warpath, burning homes and crop fields, beating women and hanging men. He was evil, personified, and fiercely despised throughout the colonies for it. In fact, at the surrender ceremonies in Yorktown, Tarleton was the only officer from either side who was explicitly excluded. He even asked if a mistake had been made, and was promptly shut down.

The First American Civil War

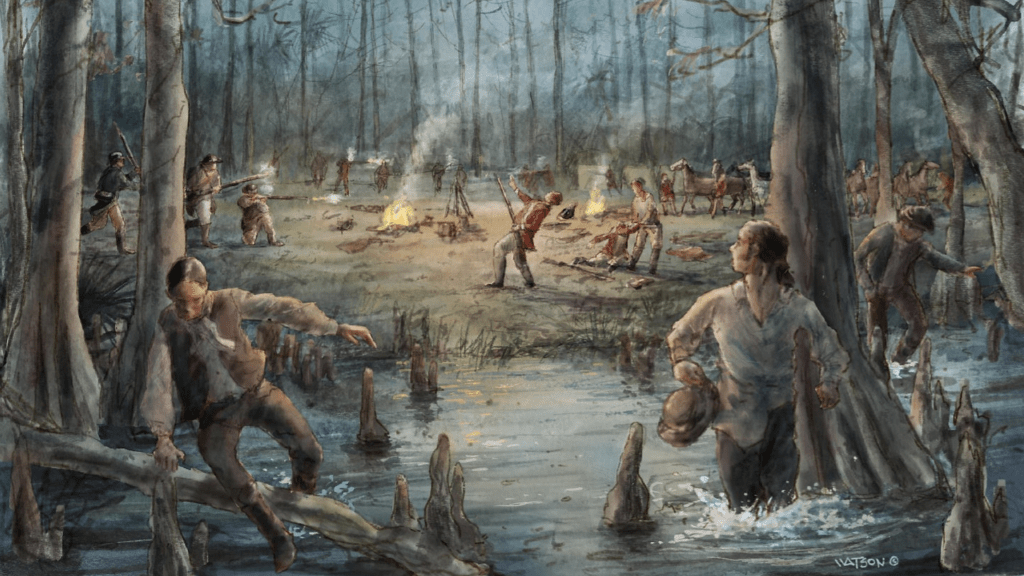

While The Butcher came to personify the despicable evil that had been unleashed onto the colonists, South Carolina had descended into full blown civil war.

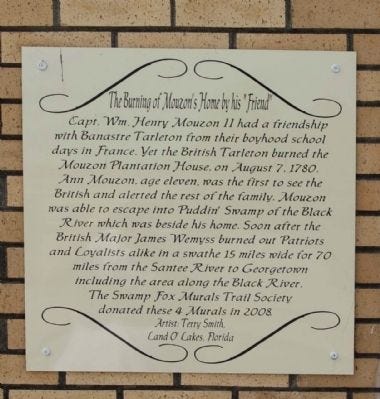

The Tory militias were going door-to-door, searching for patriot sympathizers to hang, seizing food/supplies, burning homes, and even murdering unarmed women. On multiple occasions, Banastre Tarleton’s men were accused of rape and found guilty by British military tribunal. Many of the men serving in units like Tarleton’s were colonial loyalists; meaning most of the ruthless violence being committed in South Carolina was being conducted by the colonists’ own neighbors.

The Patriot militias responded with equal brutality; fewer and fewer prisoners were being taken. The carnage was reciprocated by both sides.

Cornwallis’s plan had succeeded. The Carolinas had become an uncivilized hellscape of war and savagery. More than 200 battles took place in this colony—more than any other— and most of them occurred after the British invaded in 1780.

The Art of War

What made Marion truly stand out among his peers was not his use of battlefield tactics. It was his tactics off the battlefield. Not only in the treatment of his own men, but also the enemy, as well.

When it came to his own troops, Marion always had a pulse on the state of morale. He would plan actions around it. Attack when morale was high; Regroup and resupply when it was low. He would send men back to their homes to check on their families, when their anxiety seemed to consume them. Despite lacking any real charisma or charm, Marion understood people in a way that few military commanders perhaps ever have.

Marion was operating without any logistical support from any government or military authority. All he had were the men around him; it was imperative that their hearts and minds remain in the fight.

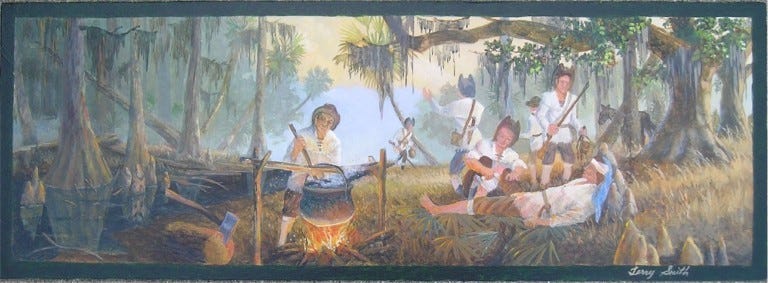

In one notorious anecdote, a young British officer was sent by Cornwallis with white flag in hand to parlay with Marion. He was blindfolded by the intercepting scouts, and led through the swamps to the patriot camp. When his eyes were uncovered, he was surrounded by what appeared to be Robin Hood and his motley outlaws. The young officer witnessed an idyllic scene of brotherhood and camaraderie: men lounging in the shade, reading books to one another, playing music on makeshift instruments, and playing boyish sports, while the horses—though saddled—grazed peacefully in the tall grass.

These did not look like men at war. These were men at peace with themselves and the burning hellscape around them.

When Marion asked the young officer to join them for dinner, he was quick to accept, intrigued by the gravity and respect this tiny man commanded from everybody around him.

The food was not fancy—roasted potatoes served on plates of tree bark—but Marion joked that “hunger is the best sauce.” The young officer was overwhelmed by the encounter, being a young aristocrat raised with the lavish refinements of England, witnessing men without possessions and driven from their homes by fire find such peace in the chaos of war. As the legend goes, that returning to the British camp, he immediately resigned from the army, and departed for home, “declaring his conviction that men who could with such content endure the privations of such a life, were not to be subdued.” (Simms 121)

![The Patriot: Gabriel Martin [ESFP 1w2] – Funky MBTI The Patriot: Gabriel Martin [ESFP 1w2] – Funky MBTI](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F705b363a-46e5-4433-b312-01e1a81a688c_815x491.jpeg)

Marion’s Psywar

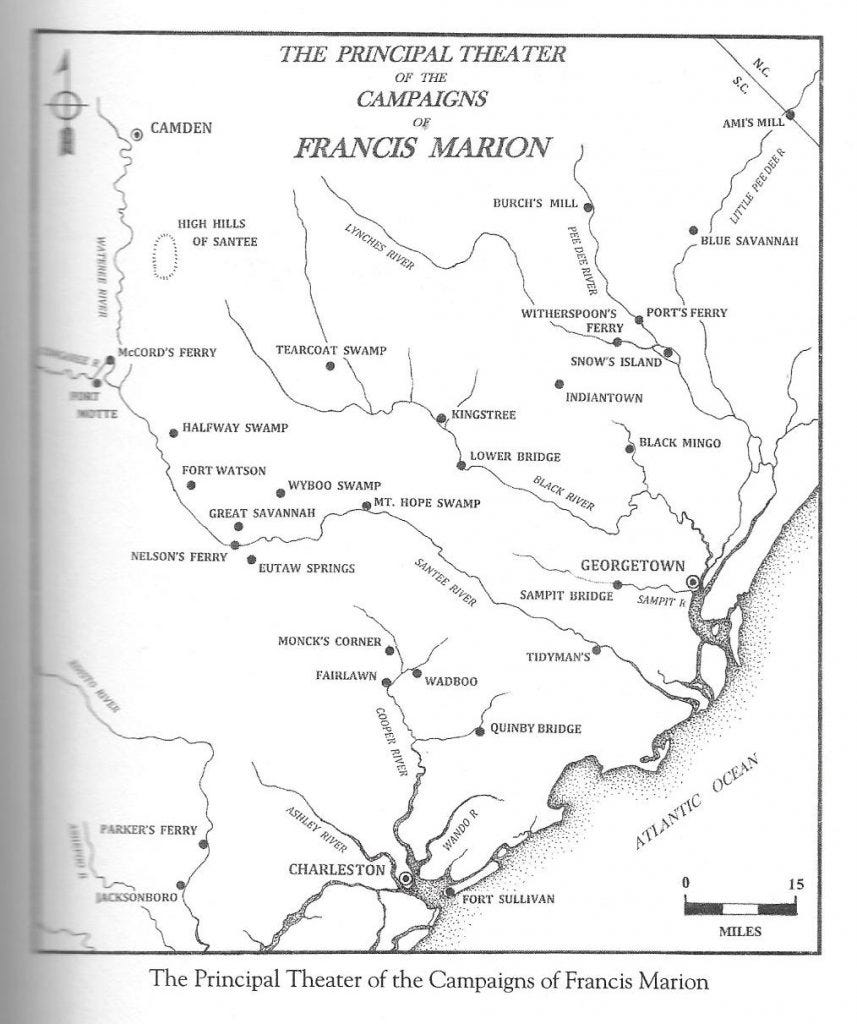

What is noted by all students of Francis Marion was the psychological impact of his guerilla campaign on the British. He took what few men he had, and spread them out over an enormous area. (See map above.)

The result was that Cornwallis vastly overestimated the size and resources of Marion’s forces, and became much more conservative as a result, especially after Marion seized a wagon full of his personal writings and affects.

“Target the officers …”

Marion also instructed his men to use their first shot fired from cover to target the British officers— the highborn—riding in file. When confronted by the British for this egregious offense during one of their many parlays, Marion retorted that as long as the British continued burning homes and harming women, he would continue to assassinate the British leadership.

The British insisted that these were two separate issues, and Marion insisted that they were one in the same.

Death by a Thousand Papercuts

Marion succeeded in containing Cornwallis in South Carolina long enough for the French fleet to arrive and reinforce George Washington in Virginia. Marion also provided a template to his colleagues on how to fight the most powerful army on earth—using the Fabian strategy, and irregular warfare. It was very Sun Tzu-esque, as a war of attrition is normally implemented by the side with greater resources to bleed out the smaller army.

Have Faith in Humanity

Marion’s notorious good treatment of prisoners became an asset at the closing of the war. As Tory militia leaders began to see the writing on the wall, they would come to Marion with terms of surrender, knowing that he wouldn’t hang them. Universally, it was always the wives and children that these Tories expressed concern for—making sure they were protected and cared for, while they faced whatever consequences awaited them on the other side of the Yorktown surrender.

They only trusted Marion with their families, many of whom were in hiding.

This is the important point with which I wish to end this first chapter.

Throughout the entire conflict, Francis Marion continued to see the humanity in the Tories. Even as his home descended into a bloody civil war, and his own loved ones were killed, he recognized that these neighbors would still be his neighbors after they drove out the British and became an independent nation.

Some of Marion’s own men defected to the Tories, this is true. But it was always Marion that Tory defectors sought out for leadership, because that’s what he was: a true leader of men. (Not a blood-thirsty warmonger, like Banastre Tarleton.)

There are so many lessons to be drawn from the chronicles of Francis Marion, which is why he is the founding father of this series. As excited as I am to tell these tales, I’m even more excited to flesh out these lessons, and apply them to our modern conflict.

We are now fighting the same simultaneous two-front war that was raging in colonial South Carolina: a brutal civil war between neighbors, and an existential struggle against a subjugating oligarchy that intends to conquer us all. We must master the fight on both fronts, and make quick peace with one rival so we can together vanquish the greater enemy.

That is the mission.

Epilogue

The purpose of this series is not to convince you to believe in me or my interpretation of history. The purpose of this series is to convince you to believe in yourselves, and more importantly, in each other.

You now face the same unenviable decision that your ancestors faced in 1775: submit or revolt.

Should you choose the latter, you must also choose to believe in each other; Because without each other, you cannot succeed. You will fail, regardless of whatever Donald Trump and the patriots behind him have up their sleeve.

You must choose to come together—not just as conservatives, or Christians, or Trump-supporters—but as American Patriots. If we are to weather this storm, we must build a real coalition strong enough to become the fist of reckoning against the globalist oligarchy. That will mean making peace with our rivals, so that, together, we can destroy our common enemy.

Devolution is the anvil, President Trump is the hammer; We The People must now become the blacksmith’s arm that wields it. That is what my next article will address, in lieu of Chapter 2.

In the meantime, recalibrate your minds for the 5GW battlefield. Follow in the footsteps of Francis Marion, and become partisan guerillas in the swamps of cyberspace. Harass and frustrate the enemy’s efforts to deploy narratives designed to subjugate the minds of our people. Sabotage their messaging; flood the airwaves with counter-narratives; reek havoc on their psyche. Look to Chris Paul for leadership. Let him be your militia captain. (Then become one, yourself.) Learn to work together, and coordinate an effective 5GW counterinsurgency.

Don’t take it from me, listen to the Boss:

He ain’t talking about violence. (What would Francis Marion do?)

Ridicule is the bane of all tyrants. Humor is your weapon. Aim small, miss small.

Godspeed.

In the next chapter of the Patriot Chronicles…

“I have not yet begun to fight!”

So you think Han Solo is cool? A rogue outlaw turned war hero? Who happens to be one of the best pilots in known existence? Whose courage was so stout that his actions blurred the line with foolish? Whose contemporaries thought was a madman?

What if he was a real person, but with a Scottish accent?

What kind of a madman sails a single ship against the most powerful navy of all time? And then into the enemy’s homeport, looking for a fight?

Fight? Yes.

Works Cited

Oller, J. (2018) The Swamp Fox: How Francis Marion saved the American Revolution. New York, NY: Da Capo Press.

James, W.D. (2013) Swamp Fox: General Francis Marion and his guerrilla fighters of the American Revolutionary War. United States.

SIMMS, W.G. (2019) Life of Francis Marion: The swamp fox. SUZETEO ENTERPRISES.

The life of general Francis Marion : A celebrated partisan officer in the Revolutionary War, against the British and Tories in South Carolina and Georgia : Weems, M. L. (Mason Locke), 1759-1825 : Free download, Borrow, and streaming (1970) Internet Archive. Available at: https://archive.org/details/lifeofgeneralfra00weem_1 (Accessed: 21 June 2023).

Neal, J. and Segars, B. (2016) Churches in South Carolina burned during the American Revolution: A Pictorial Guide. United States.

Special thank you to Major John Keil and the Office of the Judge Advocate General for researching and publishing the war crimes of Banastre Tarleton.

Kiel, John, War Crimes in the American Revolution: Examining the Conduct of Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton and the British Legion During The Southern Campaigns of 1780–1781 (2012). Military Law Review, Vol. 213, 2012, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3291696

Badlands Media articles and features represent the opinions of the contributing authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Badlands Media itself.

If you enjoyed this contribution to Badlands Media, you can follow Ghost on Twitter and Truth Social.

A marvelous article sir, though I had known of the Swamp Fox from my own personal interests in history, there were a host of details I was unware of which your article expressed with poetic succinctness. It delivers two very crucial points to patriots, to fight tyranny means enduring incredible hardship, and the power of having principles even an enemy will come to admire and seek shelter in.

Damn this was a great read and education! Never heard such taught in elementary or in collage. MAGA!